Pyranometers: What You Need to Know

by Alan Hinckley | Updated: 06/14/2017 | Comments: 13

If you are considering using pyranometers in your measurement application, there are many things you should know about them and how they work. Having this information in hand will help ensure you select the type of pyranometer most suitable for the data you need for your application.

Note: Because of the focus of this article, I will not be covering how to measure the individual direct solar or diffuse solar radiation, or discussing the different types of radiation in depth.

What is global solar radiation?

Our sun outputs radiation over wavelengths from 0.15 to 4.0 µm, which is called the solar spectrum. The measurement of the sun’s radiation on the earth is referred to as global solar radiation. Sometimes called short-wave radiation, global solar radiation is both the direct and diffuse solar radiation received from the hemisphere above the plane of the pyranometer.

It is difficult to find an environmental process on the earth that isn’t driven directly or indirectly by the sun’s energy. Therefore, it is likely that global solar radiation affects the process you are researching.

Who measures global solar radiation and why?

Global solar radiation measurements are used in several applications for different purposes:

- Solar energy to determine how efficiently solar panels are converting the sun’s energy into electricity and when the panels need to be cleaned. Sensors used for this purpose usually measure radiation in the plane of the solar panel array.

- Utilities to predict gas and electricity energy usage

- Research as one parameter to predict or quantify plant growth or production

- Agriculture, as well as golf and park maintenance, as one parameter to predict plant water usage and to schedule irrigation

- Meteorology as one factor in weather prediction models

What is a pyranometer, and what does it do?

A pyranometer is a sensor that converts the global solar radiation it receives into an electrical signal that can be measured. Pyranometers measure a portion of the solar spectrum. As an example, the CMP21 Pyranometer measures wavelengths from 0.285 to 2.8 µm. A pyranometer does not respond to long-wave radiation. Instead, a pyrgeometer is used to measure long-wave radiation (4 to 100 µm).

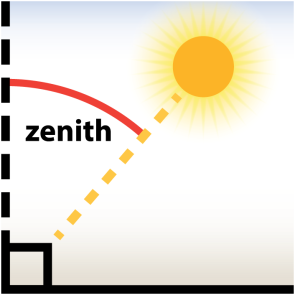

Pyranometers must also account for the angle of the solar radiation, which is referred to as the cosine response. For example, 1000 W/m2 received perpendicular to the sensor (that is, 0° from zenith) is measured as 1000 W/m2. However, 1000 W/m2 received at an angle 60° from zenith is measured as 500 W/m2. Pyranometers that have diffusors instead of glass domes require precise diffusors to provide the correct cosine response.

A pyranometer with a diffusor |

A pyranometer with a glass dome |

What is the difference between a pyranometer, a net radiometer, and a pyrheliometer?

There are several different types of solar radiation sensors, including pyranometers, net radiometers, and pyrheliometers.

A net radiometer measures incoming and outgoing short-wave radiation using two thermopile pyranometers, and it measures incoming and outgoing long-wave radiation using two pyrgeometers. These four measurements are frequently part of an energy budget. Energy budget assessments help us understand whether solar energy is being stored in the ground or lost from the ground, reflected, emitted back to space, or used to evaporate water.

A net radiometer

A pyrheliometer consists of a radiation-sensing element enclosed in a casing (collimation tube) that has a small aperture through which only the direct solar rays enter. Radiation bounced off a cloud or particle in the air does not make it through this small opening and collimation tube to the detector. To make measurements all day, a pyrheliometer needs to be pointed directly at the sun using a solar tracker.

A pyrheliometer

How does a pyranometer measure global solar radiation?

The most common types of pyranometers used for measuring global solar radiation are thermopiles and silicon photocells (Tanner, B. “Automated weather stations," 73-98). These pyranometer types are discussed below, along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Tip: You will need to connect the pyranometer to a digital multimeter or data logger programmed to measure the mV dc voltage.

- If you are using a digital multimeter, you’ll need to convert the mV reading to W/m2 yourself.

- If you are using a data logger, you’ll need to set up the data logger to make the conversion.

There are also pyranometers on the market where short-wave radiation (W/m2) is returned in digital format. This will require either a computer or data logger to read the serial data string (along with the appropriate interface data cable and communications software).

Thermopile pyranometers

Thermopile pyranometers use a series of thermoelectric junctions (multiple junctions of two dissimilar metals—thermocouple principle) to provide a signal of several µV/W/m2 proportional to the temperature difference between a black absorbing surface and a reference. The reference may be either a white reflective surface or the internal portion of the sensor base. The thermopile pyranometer’s black surface uniformly absorbs solar radiation across the solar spectrum.

The solar spectrum is the range of wavelengths of the light given off by the sun. Blue, white, yellow, and red stars each have different temperatures and therefore different solar spectrums.

Our yellow sun outputs radiation in wavelengths from 0.15 to 4.0 µm. The thermopile pyranometer accurately captures the sun’s global solar radiation because its special black absorptive surface uniformly responds to most of the solar spectrum’s energy. The sensing element is usually enclosed inside one or two specialty glass domes that uniformly pass the radiation to the sensing element.

The advantages of thermopile pyranometers relate to their broad usage and accuracy. A thermopile pyranometer’s black surface uniformly absorbs solar radiation across the short-wave solar spectrum from 0.285 to 2.800 µm (such as with the CMP6 Pyranometer). The uniform spectral response allows thermopile pyranometers to measure the following: reflected solar radiation, radiation within canopies or greenhouses, and albedo (reflected:incident) when two are deployed as an up-facing/down-facing pair.

Although thermopile pyranometers can be the most accurate type of solar short-wave radiation sensors, they are typically significantly more expensive than silicon photocell pyranometers.

Silicon photocell pyranometers

Silicon photocell pyranometers produce a µA output current similar to how a solar panel converts the sun’s energy into electricity. When the current passes through a shunt resistor (for example, 100 ohm), it is converted to a voltage signal with a sensitivity of several µV/W/m2. A plastic diffuser is used to provide a uniform cosine response at varying sun angles.

The spectral response of silicon photocell pyranometers is limited to just a portion of the solar spectrum from 0.4 to 1.1 µm. Although these pyranometers only sample a portion of the short-wave radiation, they are calibrated to provide an output similar to thermopile sensors under clear, sunny skies. Silicon photocell pyranometers are often used in all sky conditions, but measurement errors are higher when clouds are present. The uniformity of the daylight spectrum under most sky conditions limits errors typically to less than ±3%, with maximum errors of ±10%. The error is usually positive under cloudy conditions.

Silicon photocell pyranometers are typically several times less expensive than thermopile pyranometers. For environmental researchers, the accuracy of silicon photocell pyranometers is often sufficient for their requirements.

The disadvantage of silicon photocell pyranometers is that their spectral response is limited to a smaller portion of the solar spectrum from 0.4 to 1.1 µm. These pyranometers perform their best when they are used to measure global solar radiation under the same clear sky conditions used to calibrate them. They should not be used within vegetation canopies or greenhouses, or to measure reflected radiation.

A Comparison of Pyranometers

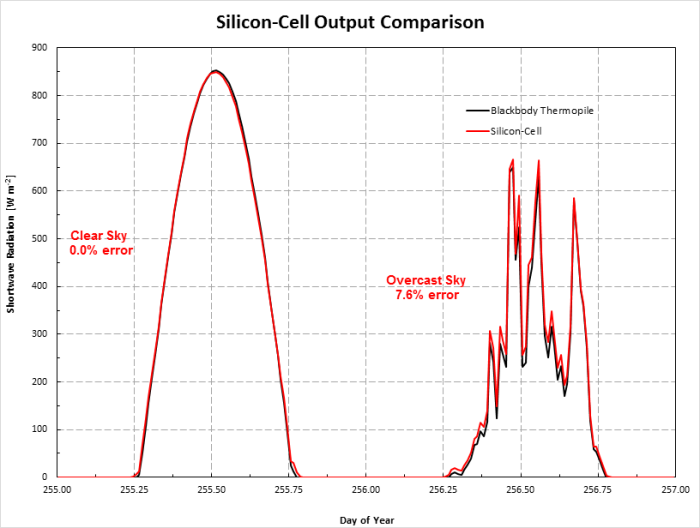

The following graph shows a comparison between the measured output of an inexpensive silicon-cell pyranometer and a secondary-standard blackbody thermopile reference sensor on both sunny and overcast days:

Because the silicon-cell sensor is calibrated under sunny, clear-sky conditions, it closely matches the higher-end sensor in those conditions. However, because the silicon-cell sensor only subsamples solar short-wave radiation (0.4 to 1.1 µm), errors are introduced when the sky conditions change. This particular sensor reported a positive 8% difference from the reference on an overcast day.

What are the different classes of pyranometers?

The WMO (World Meteorological Organization) has established the World Radiometric Reference (WRR) as a “collective standard.” "The WRR is accepted as representing the physical units of total irradiance within 0.3 per cent (99 percent uncertainty of the measured value).” All pyranometer calibrations trace back to the WRR.

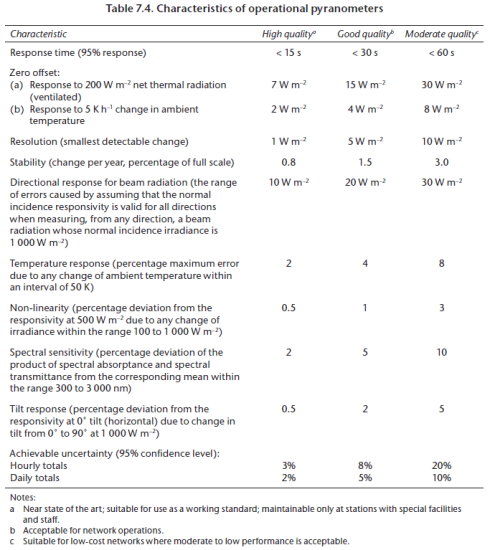

Not all pyranometers are of the same quality. Three pyranometer categories have been established by the WMO (World Meteorological Organization) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) for different applications. The following table shows the WMO pyranometer categories (Jarraud, M. “Guide to meteorological instruments and methods of observation," 233). The ISO categories named “secondary standard,” “first class,” and “second class” closely correspond to the WMO categories named “High quality,” “Good quality,” and “Moderate quality.”

There are a few differences in the WMO and ISO specifications. For example, the ISO standard for solar energy (ISO 9060) specifies a spectral range of .35 to 1.5 μm, whereas the WMO standard’s spectral range is 0.30 to 3.0 μm. In addition, the ISO secondary standard specifies 3% spectral sensitivity, whereas the WMO High Quality specifies a 2% spectral sensitivity. In the table image above, the WMO specifies “Resolution” and “Achievable uncertainty,” which are not mentioned in the ISO standard.

Conclusion

I hope this introductory article has helped familiarize you with pyranometers and what they do. I also hope you have a better understanding as to the type of pyranometer that may be most suitable for your application’s needs. If you have any questions or comments about pyranometers, please post them below.

Credits: References used to write this article include the following:

- ISO 9060:1990 Solar energy — Specification and classification of instruments for measuring hemispherical solar and direct solar radiation, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Tanner, Bertrand D. “Automated weather stations.” Remote Sensing Reviews 5, no. 1 (1990): 73-98.

Alan Hinckley provides project delivery support for Client Services at Campbell Scientific, Inc. Previously, he was the Senior Market Sales Engineer for the Hydromet Group. He has a master's degree in biometeorology from Utah State University and a bachelor's degree in chemistry from New Mexico State University.

Alan Hinckley provides project delivery support for Client Services at Campbell Scientific, Inc. Previously, he was the Senior Market Sales Engineer for the Hydromet Group. He has a master's degree in biometeorology from Utah State University and a bachelor's degree in chemistry from New Mexico State University.

Comments

GAG | 06/20/2017 at 03:34 AM

Hi, Alan

In this article, you write " Pyranometers that have diffusors instead of glass domes require precise diffusors to provide the correct cosine response.", I did not fully understand your meaning. In Apogee Instruments website, they explain it like this:

Directional, or cosine, response is defined as the measurement error at a specific angle of

radiation incidence. Error for Apogee siliconcell pyranometers is approximately ± 2 % and

± 5 % at solar zenith angles of 45° and 75°, respectively.

So Apogee have done the correction using the shape of the diffusor, but silicon photocell pyranometers still have a small error. We users don't have to do a math consine caculation, which is not see in CS300 manual. Am I right?

PS: Your article is very useful!

Thanks.

AlanHinckley | 06/26/2017 at 02:20 PM

Thank you for your comment.

Your final statement is correct. You do not have to, and should not, mathematically apply a cosine correction to pyranometer data. The sensors have already done it for you.

First, it is important to separate directional response, cosine response or cosine correction--all different names for the correction needed due to the angle of the radiation--from errors in that correction. Cosine correction is done by the manufacturer of the pyranometer so the pyranometer follows Lambert’s cosine law which states that radiant intensity is directly proportional to the cosine of the zenith angle. The directional response error or cosine correction error indicates how far off from a true cosine correction the sensor is.

A common directional response specification for pyranometers is a deviation of less than 10 W/m2 from a direct beam of 1000 W/m2 up to a zenith angle of 80°. The cosine of 80° is 0.174, so irradiance from a 1000 W/m2 direct beam is 174 W/m2 at 80°. Thus, a pyranometer with this specification should measure within the range 164 to 184 W/m2 at a zenith angle of 80°. This specification can be interpreted in terms of relative error by dividing 10 W/m2 by 174 W/m2. Thus, an absolute error of 10 W/m2 at an 80° zenith angle is a relative error of 5.7%. If the directional error specification is 20 W/m2 up to 80°, then relative error at 80° is double that for 10 W/m2 (11.4 %). For a directional error specification of 5 W/m2, relative error is half that at 80° (2.9 %).

Second, hoping to be interesting without going too deep, I would like to expand a bit more on similarities and differences between thermopile pyranometers and silicon-cell pyranometers and their effect on the cosine correction error.

Thermopile pyranometer cosine correction is impacted by the spatial uniformity of the domes and blackbody absorber and the alignment of the domes and the absorber. Similarly, silicon-cell pyranometer diffusors must be uniform and properly aligned with the silicon absorber. All pyranometer-leveling devices must be on the same plane as the absorber and the sensor must be exactly level.

The cosine response of silicon-cell pyranometers is different from thermopile pyranometers in that it also includes a spectral component due to the unique spectral response of silicon photocells mentioned in the article. For silicon-cell pyranometers, the cosine response in the field is a combination of the angular cosine response as measured in the laboratory and the spectral response of the sensor. At high solar zenith angles the angular response error is negative but the spectral response error is larger and positive. Consequently, silicon-cell pyranometers diffusors are shaped to increase the negative angular error to offset the positive spectral response error. Doing this, they can keep the total cosine response error under 5% at angles less than 75°.

The essential point is that both glass domed thermopile pyranometers and silicon-cell pyranometers with diffusors output cosine corrected solar radiation measurements. It is just a bit more work for the manufacturer of the silicon-cell pyranometers due to silicon’s unique spectral response characteristics.

abdellah | 02/04/2019 at 03:48 AM

Bonjour Alan,

j'ai trouvé votre article tres interessant. Actuellement je suis sur un projet d'etalonnage de pyranometre par cmparaison en exterieur ISO 9847, je voudrai savoir s'il y'a lieu de tenier compte de la temperature ambiante en externe dans le calcul de l'incertitude. Quel conseils pourrai vous me donner dans la mise en oeuvre de mon projet.

Thiru | 05/20/2019 at 11:15 AM

Hai Alan,

How to find out the direct and diffuse radiation from the GHI radiation.

Please let me know about clear explanation with examples.

AlanHinckley | 05/20/2019 at 02:27 PM

Hello,

Global Horizontal Irradiance or GHI is:

GHI = [Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) * Cos(zenith angle)] + Diffuse Horizontal Irradiance (DHI).

OR

GHI = [Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) * Cos(zenith angle)] + [Diffuse Normal Irradiance (DNI) * Cos(zenith angle)].

To determine the direct and/or diffuse radiation from the GHI, you must first know or measure the DNI or DHI plus the zenith angle.

Please let me know which additional information you have.

Alan

enriquef | 02/13/2020 at 09:58 AM

Hi Alan,

congrats for the great article. I find it very interesting and useful.

May I ask you for some recommended sources or literature to continue reading about the differences and similarities between thermopiles and silicon-cell pyranometers?

Thanks.

Jaume | 10/16/2020 at 04:58 AM

Hello Alan,

Thank you very much for clarifying all these aspects about different types of pyranometers. I took some measures using a silicon photocell pyranometer inside a glasshouse, but I just learned that shouldn't be done. Do you think that data is completely useless? I am trying to estimate different components of radiation (short and long wave) on a plant leaf on which I was taking other measures, all in the glasshouse. Let me know your thoughts.

Cheers,

Jaume

hmahan | 10/16/2020 at 09:26 AM

Hi Enriquef,

Refer to the CS320 webpage Documents section under Miscellaneous titled “Data from a New, Low-Cost Thermopile Pyranometer Compare Well with High-End Pyranometers”. This provides a great comparison between the two.

Sincerely,

Hayden

hmahan | 10/16/2020 at 09:27 AM

Jaume,

Silicon photocell pyranometers produce a µA output current similar to how a solar panel converts the sun’s energy into electricity. When the current passes through a shunt resistor (for example, 100 ohm), it is converted to a voltage signal with a sensitivity of several µV/W/m2. A plastic diffuser is used to provide a uniform cosine response at varying sun angles.

The spectral response of silicon photocell pyranometers is limited to just a portion of the solar spectrum from 0.4 to 1.1 µm. Although these pyranometers only sample a portion of the short-wave radiation, they are calibrated to provide an output similar to thermopile sensors under clear, sunny skies. Silicon photocell pyranometers are often used in all sky conditions, but measurement errors are higher when clouds are present. The uniformity of the daylight spectrum under most sky conditions limits errors typically to less than ±3%, with maximum errors of ±10%. The error is usually positive under cloudy conditions.

Silicon photocell pyranometers are typically several times less expensive than thermopile pyranometers. For environmental researchers, the accuracy of silicon photocell pyranometers is often sufficient for their requirements.

The disadvantage of silicon photocell pyranometers is that their spectral response is limited to a smaller portion of the solar spectrum from 0.4 to 1.1 µm. These pyranometers perform their best when they are used to measure global solar radiation under the same clear sky conditions used to calibrate them. They should not be used within vegetation canopies or greenhouses, or to measure reflected radiation.

However, I can’t comment on the accuracy of your data, but I recommend reaching out to Apogee for further information since they calibrate them.

Sincerely,

Hayden

nathanlu | 01/05/2023 at 09:57 PM

Hi Alan,

Thanks for the informative article. I am looking at an application where a photosensor is specified to measure illuminance from the unobstructed sky, and we are considering using the photosensor data as a proxy for solar radiation measurement (rather than using a separate pyranometer). The Silicon-cell graph is helpful in that I know we can at least count on a 7-8% error for overcast skies, but I'm imagining the spectral response of a photosensor will introduce furhter error. Do you have any guidance for the error that this might introduce?

Thanks!

Nathan

willB | 01/10/2023 at 06:50 PM

Hi Nathan,

Your application is highly spectrally dependent. Using different sensors with different spectral responses can be done but only if you know the solar spectrum. While we have reference spectra, the incident spectral radiation of a location changes throughout the day and is affected by changes in atmospheric constituents. It is not easy to state an error amount without much much more information and in the end, there simply may not be high confidence in this method.

Sabiha | 02/02/2023 at 09:09 AM

Hi CS team,

First, thank you for the article. It's very helpful.

I am working on the calibration of pyranometers according to standard ISO 98 47 and I was wondering how to introduce the offsets or the resolution mentioned on the technical characteristics in the balance sheet of uncertainties, knowing that those offsets are in W/m² and my balance sheet is in µv/w/ m² to estimate the sensitivity of my pyranometer.

Thank you for your time

willB | 02/02/2023 at 02:19 PM

Hi Sabiha,

ISO 9847 was recently revised (last revision was 1992) and published (this week). I requested a copy of that standard to help answer your question in more detail. Please allow me some time to access the standard.

ASTM G213-17(2023) Standard Guide for Evaluating Uncertainty in Calibration and Field Measurements of Broadband Irradiance with Pyranometers and Pyrheliometers has an appendix that is a simple to use Excel spreadsheet. You can add in the zero offset information there and see the effect on calibration uncertainty.

Please log in or register to comment.